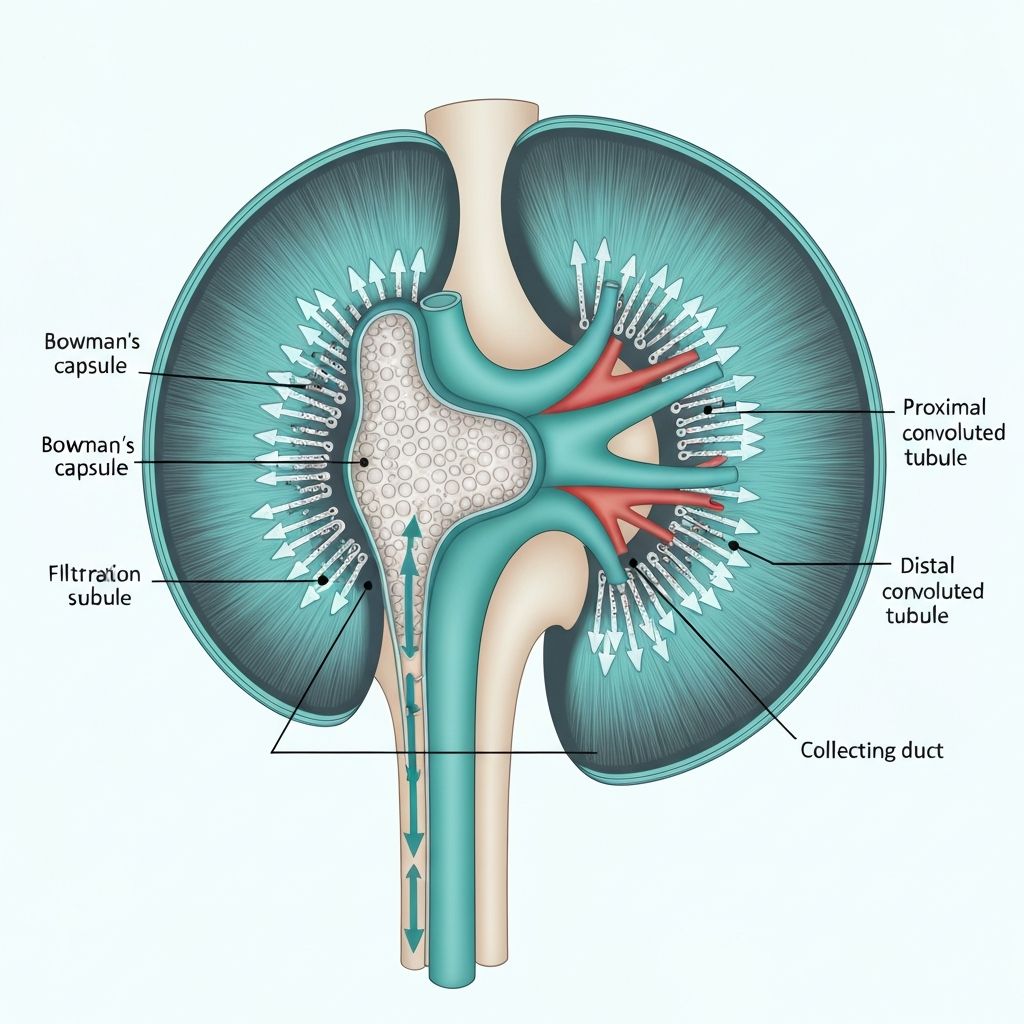

The renal tubules and collecting ducts are the primary sites of selective solute and water reabsorption. Different tubular segments possess distinct epithelial characteristics and transport capabilities, allowing fine-tuned control of substance recovery.

Proximal Convoluted Tubule

The proximal tubule reabsorbs approximately 65% of filtered sodium, chloride, glucose, amino acids, and water. Active transport via the sodium-potassium pump drives these reabsorption processes. Aquaporin-1 water channels facilitate obligatory water reabsorption through osmotic gradients established by solute reabsorption. This segment operates iso-osmotically; reabsorbed fluid osmolarity remains equal to plasma osmolarity.

Loop of Henle

The loop of Henle consists of descending and ascending limbs with distinct permeability properties. The thin descending limb is highly permeable to water but impermeable to solutes, allowing passive water reabsorption as filtrate moves toward the hairpin turn. The ascending limb is impermeable to water but actively reabsorbs sodium and chloride through active transport and cotransport mechanisms. This countercurrent mechanism establishes an osmotic gradient, concentrated in the medulla, that drives water reabsorption in collecting ducts.

Distal Convoluted Tubule and Collecting Duct

The distal tubule and collecting duct are primary sites of fine-tuned sodium and water reabsorption regulated by hormones. Aldosterone increases epithelial sodium channel expression and sodium-potassium pump activity, promoting sodium reabsorption and water reabsorption through osmotic coupling. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases aquaporin-2 water channel expression in collecting duct principal cells, permitting water reabsorption in response to plasma osmolarity.